AI Textbook-to-Quiz Generator

Fun and effective way to study History

Confidently prepare for exams with interactive quizzes that adapt to your pace.

How it works

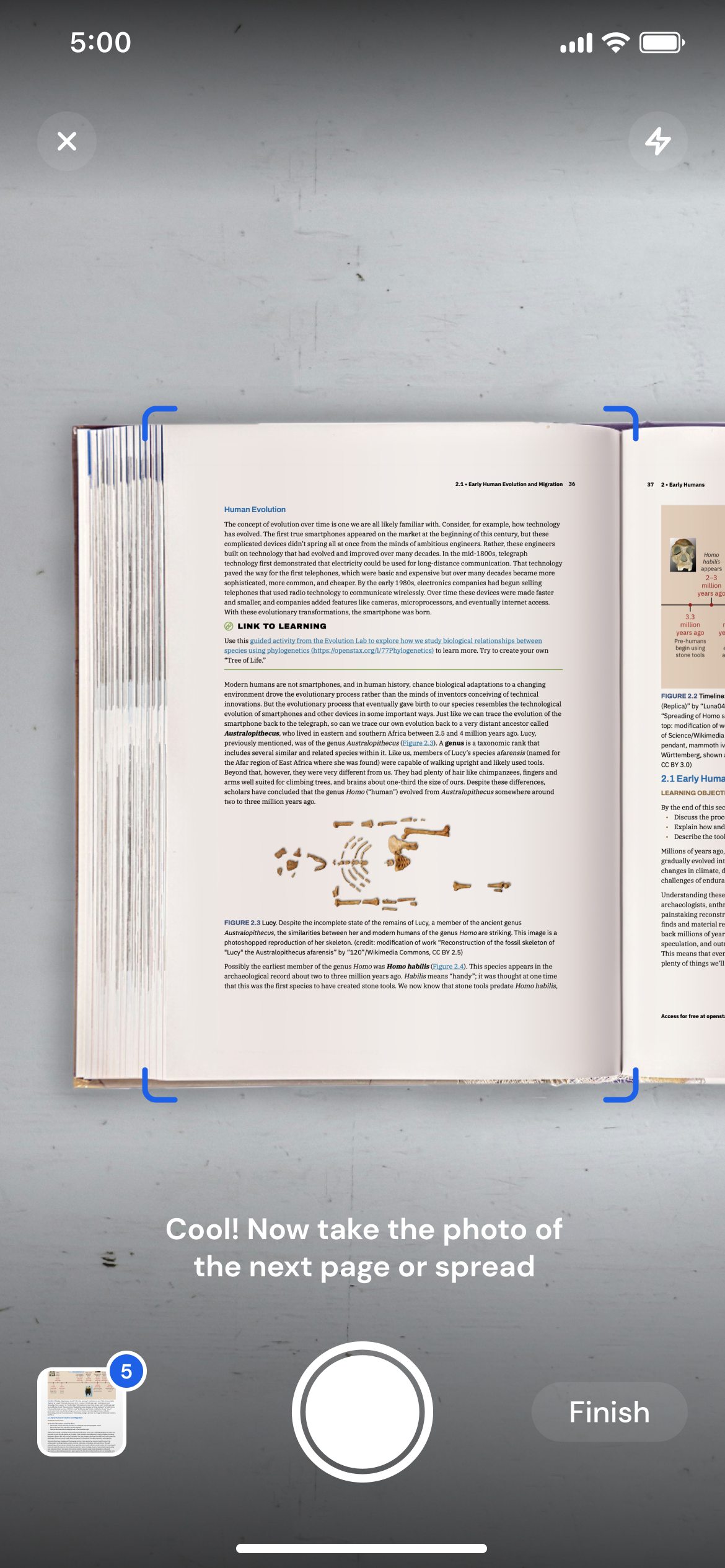

Snap a textbook chapter

Grab your textbook and snap a photo of the pages you need to study.

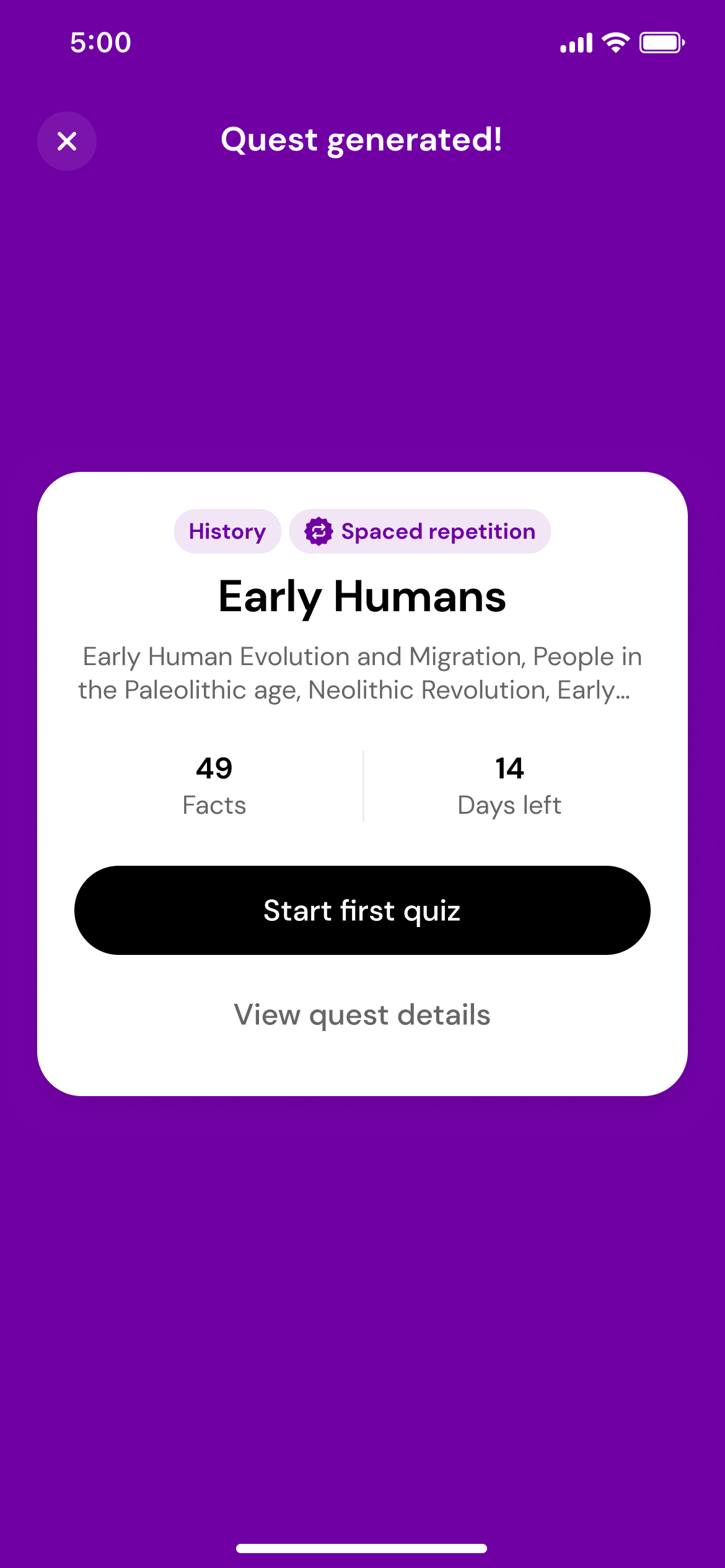

Generate a quest

Using the magic of AI, we'll transform those photos into a quest with daily quizzes.

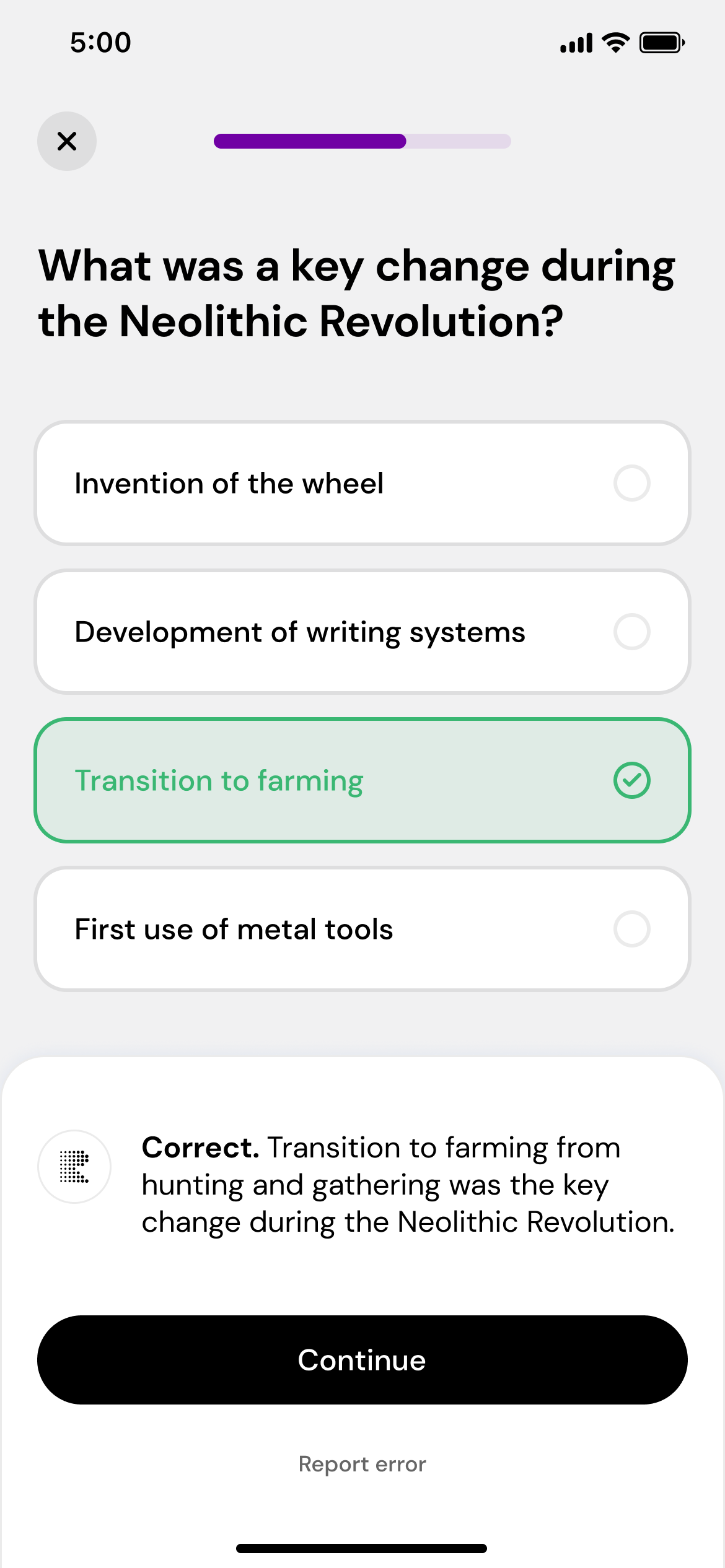

Play, learn, and repeat

Take daily quizzes that adapt to your performance, helping you master the subject.

Master challenging topics

with ease

Effortless quiz creation

Just snap a photo of the textbook, and we’ll do the rest. The quizzes match your material perfectly, so you’re always on track.

Smart, personalized quizzes

Our smart algorithm uses cognitive science to boost your learning with spaced repetition and active recall. Faster, personalized learning.

Master social sciences & humanities

Repetitio is built to simplify subjects like history, psychology, and biology.

Why students love us

I used to zone out while reading my history textbook. Now I get quick quizzes that help me remember stuff without needing to cram the night before.

Studying sociology felt overwhelming until I started using Repetitio. The quizzes are short but super effective and they adjust to what I already know.

Repetitio helps me stay consistent with bio. I get daily quizzes based on my textbook, and it honestly feels like the info finally sticks.

What I like about Repetitio is how it fits into my routine. I don’t have to plan out study sessions, it just gives me the right questions each day based on what I’m learning.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does Repetitio adapt to my learning pace?

Repetitio uses what's called a spaced repetition algorithm to adapt to your learning pace. By tracking your performance on each question, the app adjusts the difficulty and timing of questions to optimize your retention. Questions start as multiple choice and adapt based on your answers, moving to easier (boolean) or harder (open-ended) formats as needed.

What content can I use to generate quizzes or test questions?

Repetitio currently supports English, and, experimentally, French, Spanish, German, Italian, Polish, and Portuguese textbooks, focusing on narrative content. It's ideal for subjects like humanities, social sciences, biology, and other narrative driven subjects. It doesn't support subjects like physics, mathematics, or foreign languages.

Can I customize the types or difficulty of questions in Repetitio?

Repetitio automates the question-generation process. It converts textbook content into simple, factual statements and creates questions in boolean, multiple choice, and open-ended formats. The app selects the question type based on your previous performance, without the need for manual customization.

How does Repetitio calculate my readiness for an exam?

Repetitio uses various metrics to track your learning progress. With this information, it estimates your current readiness level which corresponding to how well you might perform if you were to take an exam today.

Which languages are supported by Repetitio?

Repetitio currently supports English, and, experimentally, French, Spanish, German, Italian, Polish, and Portuguese. However, we are always working hard on adding more languages!

Which subjects are best suited for Repetitio?

Repetitio is most effective for humanities, social sciences, biology, and other narrative driven subjects. It's not designed for physics, mathematics, or language learning.